Growin' Up in West Virginia

REMEMBRANCE OF THINGS PAST

Part One: Wore I Come From

I was born and I growd up in Beckley, a small, coal mining town in West Virginia in the mountains of Appalachia. (Some old folks up in the hills still pronounce Virginia, “Virginie”.) That part of Appalachia's first settlers were Scots-Irish, who arrived in the late 1700s and early 1800s. They were mostly Protestants from Northern Ireland. They were known for family farming and raising livestock. They brought with them their cultural traditions, including music, crafts, and storytelling. Their language, with some of its peculiar accents, persists even today. Most people back then were rural, white folk. I never seen any Black folk in Beckley although there might have been a few. The white folk back then called them Coloreds when they were being polite, and another name I will not repeat when they were being nasty. I learned in college not to use either of those names—Blacks or African Americans was considered to be the correct names.

Part Two: Fanny

Most of my relatives were poor people, a tight-knit group wary of outsiders, and loyal to their blood kin. They all consider me "family" even though they saw me as "different" in a lot of ways. I don't remember much about growin' up there. I just did what all the other kids did until I realized I was not like them. Not to say I was better, just that I was different. I left Beckley as soon as I was old enough to see what a dead-end town it was.

Most families back then were large; 10-12 kids was common, and most women married young. You see, there warn't no contraceptives back then and families used their kids to help work and maintain the household. My grandma Fanny was the unspoken matriarch of our group. She had 10 kids, but her five-year-old daughter died from some kind of disease. All the other kids grew up fine; there was an equal mix of boys and girls. None got much schoolin'. Uncle Jimmy became a plumber, Lee became a barber, uncle Gary joined the Army. Uncle Willard was the most successful. He became some kind of businessman in town. All of my aunts learned household skills like sewing, darning, knitting, cooking while waiting for some young men to marry them. Hardly anyone divorced back then. Even if you wound up hatin' the guy you married, you stuck with him. Back then couples needed each other to make ends meet.

Most of us were Crocketts and McBrides, but there were other last names due to marriages.

Fanny's husband Lonnie Lee McBride worked for the railroad repairin' locomotives and freight cars. He was killed before I was born when a heavy piece of machinery fell on him. Fanny and the kids must have been heart-broken for years.

Fanny's little house was up on a hill next to one of the one-lane roads that led into town. Her house might of had electricity, but I don't remember. It had nothing to heat it during the winter and no running water. There was a well just behind the back porch with a ladle on a hook and a handle to bring up a pail of water. It was the best tastin' water I ever had.

The front room in Fanny's house was her "parlor". None of the kids were allowed in there. It was for visitin' like when the local preacher came over on Sunday afternoons to sit and flirt with Fanny. The room had the best furniture—a pretty good sofa and a lamp on an end table. There was an old black Bible on the table. I don't think anyone read from it. It was just used to hold family photographs and notes about when and how relatives had died.

Further back of the house was Fanny's big garden, and what a wonderful garden it was. That's where most of the family's food came from. Fanny growd just about everything, like potatoes, hickory king corn, rutabagas, creasy greens, hill onions, collards, and green beans. It took a lot of work to keep up the garden but is was worth it and it was necessary. The soil was rich and the only water it needed was rain.

Fanny also had a pigpen next to the garden. Once a year some of the pigs were killed and butchered. The meat was cured with salt and smoked in the smokehouse next to the pen.

There always were fresh eggs because there were lots of chickens running around during the day and roosting at night. There also was a nasty rooster who strutted around all the time crowing like he was the King of Siam, whoever that was. The minute you came out the back door, he'd come running at you and peck the shit out of you. One day when I was visiting he was particularly obnoxious. My uncle Gary got mad as hell and brought out his shotgun and blowd away the rooster's head and some other body parts.

Out in the scrubland further back of the property grew possum pine, hackberry, and scrub oak. But what us kids always looked for when we wandered around back there was chinquapin shrubs. When the nuts were ripe, we'd eat handfuls like buzzards on road kill.

There was another building apiece from Fanny's house. It had a roof, wood sides, and a floor. There were a few cinder blocks used to step up to the door. There warn't any windows, heating or electricity. It's where Fanny's boys slept on smelly old mattresses. (The girls slept in the main house with Fanny.) Some of the boys thought boogers (ghosts) roamed around that house at night. It was cold as a witch's tit during the winter. That's when the boys would sleep in their clothes on the mattresses huddled under old, scratchy wool blankets. They farted a lot during the night, so the place was really smelly by morning.

If you needed to take care of business, you'd need to trot down to the outhouse, a small wood framed shed with a door and a small window. Inside was a small bench with a hole in the middle where you relieved yourself. It was always a good idea to check for black widow spiders before you sat down. Next to it was a barrel of dried corn cobs for wiping yourself, and an old, ragged Sears & Roebuck catalog to read if you were so inclined. Using the outhouse during the dead of winter called for mustering up a lot of gumption.

Every month or so, all of us would get together at Fanny's house for a pot-luck supper. (It always was "supper", never "dinner".) It was a feast 'cause all the wives were good cooks, but they all knew Fanny was the best cook. All of the men would sit around talkin' while the women worked in the kitchen to get the food ready. There always was lots of ham, fried chicken and a big pot of brown beans seasoned with salt pork, plus mashed potatoes, green beans, potato salad, slaw, collard greens, Jell-O salad, and cornbread. The only condiments on the table were salt, pepper and a bottle of ketchup.

Warn't no alcohol served at the supper table, just sweet iced tea in a couple of large glass pitchers. But if you were so inclined, you could get a snootful of homemade hooch by goin' out on the back porch where my uncle Jimmy usually was sittin' in an old rocking chair. Down on the floor next to him was a Mason jar filled with a clear, oily looking liquid. Jimmy made it with his Daddy's still. It went down like blue blazes. If you took a few swigs, after the coughing subsided, all you wanted to do was sit on the porch steps and look at the stars and lightening bugs. If you drank even more, you started wantin' to kill somebody.

Jimmy was proud of his corn whiskey. When he was younger and homemade booze was illegal (and I guess it still is), he would make good money hauling it over the mountains to sell it in big cities. All the feds and local cops knew him. Lots of times they would hide their cars out on the highway and wait for him to make a late night run. But they never caught him. He was just too damn fast. He did serve 11 months once in a federal penitentiary after his arrest at his daddy's still.

Jimmy loved to talk about his Ford flathead V-8 with modifications that he used for haulin' his alcohol. It had a one-brake wheel. He could go down the road, hit that brake and turn around in one lane of a highway and head back the other way at great speed. Top speed was 180 mph loaded or unloaded, uphill or downhill—it didn't matter. Jimmy attached a pair of toggle switches just left of the steering column that, when flipped, cut off the brake lights, or the taillights, or both. More than one pursuing lawman after not seeing Jimmy's lights, ended up in a roadside ditch after overdriving a curve while on Jimmy's tail. Jimmy also installed a false bottom to conceal the alcohol and carried live chickens on top as a distraction. His Ford also had an ultra-stiff rear suspension to conceal the weight of more than 100 gallons of white lightning.

Part Three: A Kid Growin' Up in West Virginia

Most of my relatives never left Beckley. My mother has been a child raiser all her life. She married when she was sixteen and had my brother when she was 18. She had four kids. My brother was four years older than me, and he used to beat me up regular when we were kids. (He learned to be mean from watching our father being mean.) After he growd up he became a local banker in Beckley. We never had no use for each other. He died a few years ago from dementia. I also had a fat younger sister I never liked at all. She married an ignorant, boorish ex-marine. When they came to visit he mostly would sit around and smoke cigarettes in the house. Our mother didn't like that, but she never said anything to him 'cause she was afraid of him. My sister and him had lots of babies. She was nothing more than white trash as far as I was concerned. My other younger sister was a sweet girl and the only sibling I could relate to. She was smart enough to stay low key and avoid our father until she was old enough to live on her own.

Whenever my brother or me got into trouble—and it was never big-time trouble—our mother was the first to know about it. When she saw us all she would say was "Wait 'til your father gets home". That meant we were gonna get a whoopin'. We had to wait until supper was over, then our father would take us into the bedroom, make us pull down our pants, and bend over the bed. Then he would take off his belt and whip our butts until he decided we had been punished enough.

My father was a complicated man, but not in a good way. He never grew up emotionally, and there's a reason for that. When he was a little boy his parents divorced. His daddy was a preacher man and a fiddler who abandoned him. So did his mother. She was a mean woman. So he wound up being raised by his maternal grandparents in a mining camp in Pennsylvania. You had to be tough to survive there and my father learned to be tough. I don't know how he and my mother met and married when he had growd up, but soon afterwards he enlisted in the military, like so many other young men, and entered WWII in the Pacific.

When my father got back from the war he was in ways a broken man, like so many other GI's. He never talked about his experiences in the war—not until he was old and suffering from dementia. I think he became paranoid because of the war. Even the slightest noise around the house could set him off. He kept a cop's billy club under his pillow at night. He found good work in town and supported our family, but he never learned how to be a good father. Our mother became his surrogate mother and took care of him, us kids and the home. I never saw my father hug or kiss my mother, certainly not hug or spend any time with us kids. He loved cars, and on weekends he often tinkered with his car in the garage. When he got older he started playing golf.

My mother was a simple country woman. Almost all of the women in her generation knew their place was in the home taking care of their husbands, raising the kids and doing all of the household chores. It was rare for a woman back then to have an outside paying job. My mother was an unemotional person. She didn't kiss or hug us kids or spend any fun time with us.

There aren't many childhood friends I can remember, but there was a few. One was Weezie. She lived a few houses down from me. I never knew her real name, and, being a kid, it didn't matter. (My nickname was Bug. Why I don't know.) We hung out a lot in my backyard. She was a tomboy through and through. During the summer she was always barefoot and—I swear it!—she could pick up honeybees between her toes and not get stung. Sometimes when we were preteens, we would talk about showing each other our privates, but we didn't have the guts to ever do it. When she grew up, she became a teacher. She never married, which surprised me 'cause she was quite pretty.

Then there was J.D. Everybody done forgot his real name—he was just J.D. I think he finished junior high, but I ain't sure. He was one of those low IQ kids just not suited for school. He never amounted to much. Even now he lives with his elderly mother, and all he does is odd jobs around town. Ain't an available local woman— and there ain't many— who'd take a second look at J.D. But he was sweet, always friendly and eager to spend time with you. I'm sure he's still a virgin. I don't think he ever had a sexual urge in him.

During the summer I earned a few dollars every week or so mowin' neighbors' lawns. As soon as I got paid, I got out my old Schwinn bicycle. (Nobody ever had a new bike; everything was used and resold.) My bike was a one-speed with a coaster brake and fat tires. That's the only kind of bike you could get back then. So I would set out to town. My first stop was the ESSO filling station. Inside it had a standing cooler filled with ice water and soda bottles. I usually would pick up a grape Nehi and pop the cap with the opener on the side of the cooler, but occasionally I would opt for an RC Cola, just for a change of pace. (A soda back then cost 10 cents.) Then I went over to the candy counter and bought a Moon Pie. Ah! That was the life.

Sometimes, when I could wheedle some extra change from my mother, I would pedal into town and head over to the Woolworth Five and Dime. It had a soda fountain in the back of the store. I would get up on one of the red cushioned stools and order a hotdog and a sundae. Oh boy!

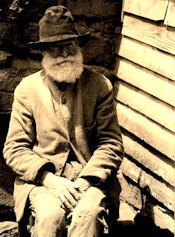

One day in town I met up with J.D. He usually was goin' in and out of stores asking for work. We sat down on a bench and he told me about a guy he knowd. He said his name was William, but everyone called him Billy even though he was an old coot. J.D. said Billy had been a pilot and now lived on the outskirts of town. I got curious, so I pedaled out to where J.D. said Billy lived. I found him at an old, ramshackle house with big weeds all over the front yard. There he was sittin' in a chair on his porch with an ugly dog fast asleep. He was a skinny guy wearin' tattered clothes and an old hat. He had a big white beard and a wrinkled face. I figured out that he must have lost quite a few teeth over the years 'cause when he opened his mouth there were a lot of gaps and what teeth remained were a dull yellowish-brown. When he smiled... well, you get the picture.

I told him my name and asked him if he really was a pilot. He just grinned. Then he lit up and started telling me stories about himself. I guess not many people stopped by to see ol' Billy, so he probably was lonely. Turns out he once was a crop-duster and made a pretty good living at it, but all the chemicals he sprayed started messin' with his breathing so he quit. He said he still had his plane in a storage hanger at the Beckley airport. He said it was a Keystone Puffer biplane, which sounded impressive to me. Nowadays he has a little repair shop where he fixes mechanical stuff people bring in for fixin'. He also sharpens knifes and scissors and repairs vacuum cleaners. I enjoyed listening to Billy's stories, and I decided to visit him again sometime.

Part Four: Gettin' Educated

After high school I decided to go to college. At first it was just a whim—something different to do. Then I realized it was a better option than gettin' a job at the local sawmill, the railroad, or moving out to a coal mining camp for work. No one else in my family ever went to college. My father paid for all of my tuition, books, and stuff, I don't know why 'cause he never seemed to like me much.

I had no idea what to do in college. I was not ambitious, and I didn't have a game plan. I did my best to improve my language so I could fit in—both how to talk and write. It was hard 'cause, er, I mean because the dialect I learned growin' up was ingrained in me. I met a lot of different people in college—both students and professors. It helped me overcome a lot of my provincial thinking and attitude. During my freshman year I had to stay in a dorm, and it was full of kids from all over the place. I remember a few of them.

There was Sassan Bourbour, a rich, arrogant Iranian guy whose family sent him to the States to study engineering. Sometimes on weekends he would go downtown to the slums in Knoxville and use his fancy camera to take pictures of the substandard housing. He would send the pictures to his family in Iran to prove to them that all Americans weren't rich.

Another character on the dorm floor was an older guy who stayed to himself most of the time. I didn't know his name, but I knew he was at least 21 years old because he could legally buy alcohol. He often would walk into town, go to the nearest bar when it opened and have a few beers with some pickled eggs kept on the counter in a big glass jar full of a milky green liquid. That was his usual breakfast. I never saw the guy go to any classes; I think he was one of those "forever students".

Likewise there was Fritz Bonner. He was a much older black fella who shaved his head everyday in the communal bathroom and walked around in a flannel bathrobe. Fritz said he was an art major, but like that other guy, I never saw him go to any classes. And I never so him wearin' any clothes except his bathrobe.

I had no idea what to study in college, but it was certainly not engineering—that was for highly motivated brainiacs. I looked through the catalog of courses and finally decided on Geology. It seemed simple enough. You learned about rocks and rock formations and memorized enough facts from the textbooks to pass the exams.

Part Five: Livin' on My Own

I got a degree in Geology, but it didn't help me get a job. A fellow graduate friend of mine told me about a job opening in Knoxville at an urban renewal company. I applied and was immediately hired—no resume needed, no background check, no nothin'. I had no idea what I was supposed to do and there was no one there to train me. Milton Pacheco was my boss. He was a friendly, short guy who always wore shiny polyester suits and highly polished brown wing-tips. On my first day of work he told me to get with the other surveyor and the draftsman and drive up to Eastern Kentucky. We were supposed to drive through the rundown towns and survey them for proposed urban renewal projects.

I didn't know how to do any kind of surveys, so I just went for the rides and shot the shit with the two other guys. After a while I started getting anxious 'cause I hadn't created any plans. So one day when Milton was gone I went into his office and started looking around. In one of the file cabinets I found some old surveys for projects that already were completed. I took all of the surveys, went back to my desk and copied them almost word-for-word except for dates, places, etc. I submitted them to Milton who didn't even look them over. He just added them to other documents required by the federal government and sent them off to Washington. They always came back approved, Milton collected his money from the feds and everybody was happy. It took me a while to figure out that when dealing with the government they always tied contracts and payments to lots of paperwork that nobody read.

Milton paid me well for doing nothing that mattered. Even so, I got tired of my job. I quit and started looking for another job. I heard about a mining company not far away that needed a geological surveyor to complete the environmental impact of their mining projects. Well, I figured that job was right up my alley. If I could prepare bogus surveys for Milton Pacheco, I could just as easily do it for a mining company. Sure enough, it worked the same way with the government— give 'em lots of documents, get paid, and then start drilling.

During this time of my life I lived day-to-day, with no interest in doing much of anything except for getting paid for meaningless work. Every few years I'd take a Greyhound back to spend some time with my parents. I saw it as my duty as a good child. I also enjoyed spending time with my mother. One day when I was especially bored, I went to the local public library to find something to read. There was a book on one of the reading tables that caught my eye. It was called The Stranger, by Albert Camus. It was plain-written and not very long, so I started reading it.

I also looked up who Albert Camus was. Turns out he was a French existentialist who lived and wrote in Algeria, a country in North Africa. I had no idea what an existentialist was, and I don't think anybody else knew what one was. I found the book's story to be quite interesting. It was about a guy named Meursault who lived in Algiers and worked as a shipping clerk. He was a detached, emotionless guy who felt isolated from the people and events around him. The novel is famous for its first lines: “Mother died today. Or maybe it was yesterday, I don’t know.”

As the story unfolds, one Sunday, Meursault and two friends, Marie, and Raymond, went to a beach house. They had a swim in the ocean and then had lunch. That afternoon, they ran into two Arabs on the beach. A fight broke out and Raymond was stabbed. After tending to his wounds, Raymond returned to the beach with Meursault. They found the Arabs at a spring. Raymond considered shooting them with his gun, but Meursault talked him out of it and took the gun away. Later, however, Meursault returned to the spring to cool off, and, for no apparent reason, he shot and killed one of the Arabs.

I felt a lot like Meursault during my years living alone—not the killin' stuff, but everything else.

I went back to visit my parents soon before my father died. He had been suffering from dementia for years, and it was a time of extreme difficulty for my mother. She refused to put him in a medical facility, and she did her best to care for him, but it was awful for her. He didn't even remember who she was. I would take him on walks around the neighborhood when he was semi-lucid. All he wanted to do then was talk about the war. He told me everything he could remember.

He said he was stationed on an airbase the military had set up on a strategic island near Japan. When planes landed after finishing their sorties, he and other men would do whatever maintenance was needed and refuel the planes. The pilots then took off for another run at the Japanese forces. Unfortunately, the Japs, as my father called them, had set up their own base on the other side of the island. Neither side had the fire power to take out the other side. But, at times the Japanese soldiers would make nighttime raids trying to kill as many Americans as they could. Everyone was on edge all the time. My father and his comrades slept in tents at night. Whenever one of them heard something outside all of them would rush to get up and start firing their weapons as soon as they were outside.

Finally my father was placed in hospice care for his final days. He died on a Sunday, or maybe it was a Saturday, I don’t know. I was by his side when he died, and I heard his final death rattle. I felt no emotions watching him die, kinda like Meursault.